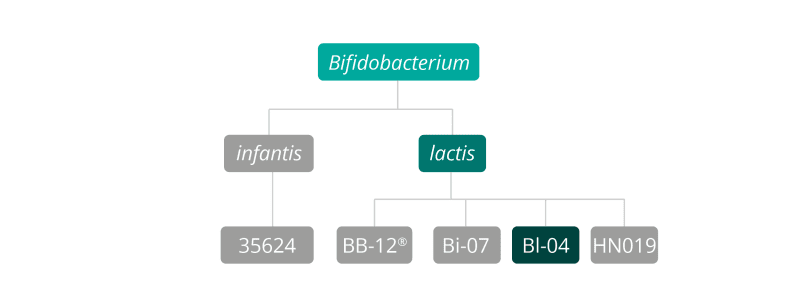

Also known as Bifidobacterium animalis subsp lactis BI-04®, this strain of probiotic is an anaerobic, gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium which can be found in the large intestines of many mammals, including humans. It has been used in a variety of studies where the focus has been to determine the potential of the strain in supporting immune function, regulating and improving gastro-intestinal function, and ameliorating the side effects of antibiotics. The Bl-04 ®strain is a member of the Bifidobacterium lactis species.

Bifidobacterium lactis Bl-04® is a strain of bacteria found in food supplements, typically as part of a combination of strains, commercially known as HOWARU Restore.

In a safety evaluation study, Morovic, W. et al (2017) assessed the HOWARU Restore supplement, which includes B. lactis Bl-04®, for various safety parameters, genomic risk factors and acute toxicity. Across all factors, all strains were found to be safe for human consumption; the acute toxicity test presented no incidences of mortality, clinical abnormalities or body weight changes related to the supplement.

Cox, AJ. et al (2014) gave B. lactis Bl-04® to one group as a food supplement (39/125 participants) over a duration of 150 days and found that it was very well tolerated with no adverse clinical events.

Forssten, S. & A. Owehand. (2017) conducted an in vitro test using a simulation of colonic survival; all strains in the HOWARU Restore supplement, including B. lactis Bl-04® was found to survive gastrointestinal conditions in vitro both a single strains and in combination.

As you will see throughout this database, the use of live cultures to support immune function is a key area of probiotic research. Mounting evidence suggests that our resident microbiome may interact with our immune system, and may even influence immune responses; further research still needs to be done to fully establish their potential benefits, but Bifidobacteria strains appear to be one of the best probiotics for this purpose.

In a randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled study, 115 participants were administered with ‘rhinovirus’ i.e. given the cold virus. The probiotic group was also given the strain Bifidobacterium lactis Bl-04® 28 days before and during the rhinovirus challenge. Results showed a reduced incidence of respiratory tract infection as well as ‘viral shedding’, i.e. the replication / spread of the virus, in the probiotic group compared to placebo (Turner et al, 2017)

A 2021 study investigated the effects of a yogurt supplemented with Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bl-04, on 136 adults with URTIs who live in a haze-covered area in a randomized clinical trial. Findings showed significant reductions in the duration & severity of URTI's in the probiotic group compared with placebo (Zhang H et al, 2021).

A human study evaluated the ability of B. lactis BI-04® to encourage a healthy immune reaction in response to a vaccination. Human volunteers were orally vaccinated against cholera, and then given either a placebo or one of seven different probiotic strains including B. lactis Bl-04® for a period of 21 days. Via blood serum and saliva testing, significant changes in immunoglobulin serum concentrations were found in 6 out of the 7 probiotic supplementation groups, whereas no changes were observed in the control group. Those in the BI-04 group showed increased IgG in an early response to the vaccine (Paineau et al. 2008).

In another randomised trial, 47 children with hay fever triggered by birch tree pollen were given a probiotic containing a combination of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM® and Bifidobacterium lactis Bl-04® or a placebo. Those taking the two strain combination were found to have a significantly reduced presence of eosinophils (a type of white blood cell which is involved in controlling allergies) in the nose area, compared to the placebo group. Additionally, the participants reported that those on the two-strain probiotic had reduced symptoms of nasal congestion and discharge, compared to those in the placebo group (Ouewhand AC et al, 2009).

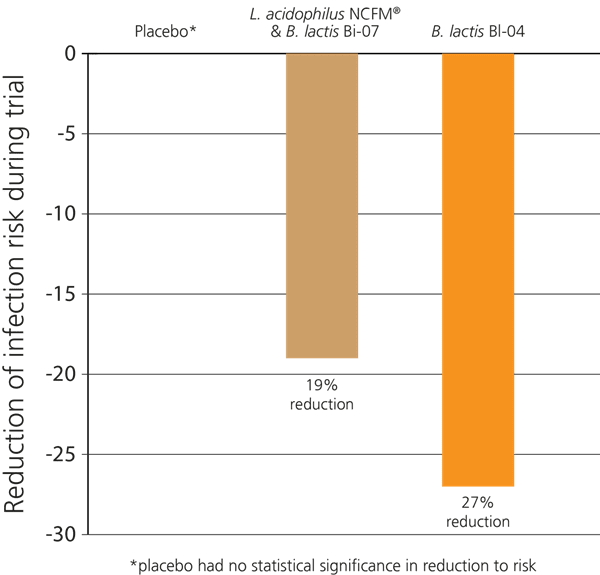

In a recent double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study in Australia, 465 healthy participants who exercised regularly were selected. The aim of the study was to determine whether probiotics would help to support immune function in these subjects, as significant exercise can put a strain on the immune system causing an increased risk of colds and respiratory infections. The subjects were divided into three groups: Group 1 were given the probiotic strain B. lactis BI-04® alone; Group 2 were given a combination of L. acidophilus NCFM® & B. lactis Bi-07®, and Group 3 were given a placebo. Over the 5 months of the trial, it was found that Group 1 displayed a 27% lower incidence of upper respiratory infections. Those in Group 2 also showed a decreased incidence of infection, though results were not as strong as in group 1; however, both groups displayed improved immunity compared to the placebo group which had no impact on infection risk reduction (West NP et al, 2014).

Other Relevant Studies: Crippsa A at al, (2014), Foligne et al, (2007), Lammers et al, (2003), Leyer et al , (2009)

In a randomised, double blind, controlled human trial B. lactis Bl-04® was a component in a five-strain formulation investigated for its ability to support the balance of intestinal bacteria during and after antibiotic therapy. This combination was found to reduce the overall disturbance of bacterial population in the gut. Additionally, this probiotic combination maintained Bifidobacteria levels at significantly higher levels than that of the placebo group, even two weeks after antibiotic treatment was ceased (Engelbreksten et al. 2009).

Another study used B. lactis Bl-04® in conjunction with another probiotic strain and the prebiotic inulin. The focus of the study was to see if giving a probiotic combination to healthy elderly patients could beneficially modulate the gut microflora. The results showed that this probiotic formulation significantly increased the levels of Bifidobacteria in the intestinal flora of the subjects.This modification of the intestinal Bifidobacteria population shows that the formulation may benefit those who have lower Bifidobacterium levels or signs of dysbiosis, e.g. higher incidence of infections and constipation (Bartosch, 2005).

Further related study: Engelbreksten et al., (2006)

A total of 510 volunteers were enrolled in a study to look at the dose dependency of the effect of probiotics on diarrhoea caused by antibiotics, or diarrhoea caused by C. difficile infection. The probiotic strain Bl-04® was tested in a supplement containing three other strains of bacteria including Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07®, L. acidophilus NCFM®, and L. paracasei Lpc-37®. Subjects were split into three groups and given either a dose of ten billion CFU of the probiotic, one billion CFU dose of the probiotic, or a placebo. It was found that the higher dose of probiotic gave the best results for the symptoms and frequency of diarrhoea, as well as for fever, pain and bloating, compared to the lower dose of probiotic or the placebo. (Ouwehand AC, 2014).

Authors: Information on this strain was gathered by Joanna Scott-Lutyens BA (hons), DipION, Nutritional Therapist; and Kerry Beeson, BSc (Nut.Med) Nutritional Therapist.

Last updated: 12th May 2020

As some properties & benefits of probiotics may be strain-specific, this database provides even more detailed information at strain level. Read more about the strains that we have included from this genus below.

Bifidobacterium lactis strains: Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07®, Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12®, Bifidobacterium lactis HN019.

Bifidobacterium infantis strains: Bifidobacterium infantis 35624.

Bifidobacterium breve strains: Bifidobacterium breve M-16V®.

For more info and the latest research on probiotics, please visit the Probiotic Professionals pages.

For products containing this strain visit the Optibac Probiotics shop.

Bartosch, S. et al., (2005). ‘Microbiological effects of consuming a symbiotic containing Bifidobacterium bifidum, bifidobacterium lactis, and oligofructose in elderly persons, determined by real-time polymerise chain reaction and counting of viable bacteria’. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 40:28-37.

Cox, AJ. et al (2014) Effects of probiotic supplementation over 5 months on routine haematology and clinical chemistry measures in healthy active adults. Eur J Clin Nutr.68 (11):1255-7

Cripps A. et al, (2014) ‘Probiotic supplementation for respiratory and gastrointestinal illness symptoms in healthy physically active individuals’ Clinical Nutrition, 33(4):581–587.

Engelbrektson, A.L., et al., (2009). ‘A randomized, double blind, controlled trial of probiotics to minimize the disruption of fecal microbiota in healthy subjects undergoing antibiotic therapy’. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 58:663–670.

Forssten, S. D., & A. C. Ouwehand, A. C., (2017) ‘Simulating colonic survival of probiotics in single-strain products compared to multi-strain products’. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 28(1): 1378061, DOI: 10.1080/16512235.2017.1378061

Foligne, B., et al., (2007). ‘Correlation between in vitro and in vivo immunomodulatory properties of lactic acid bacteria’. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13(2):236-243.

Lammers, K.M., et al., (2003). ‘Immunomodulatory effects of probiotic bacteria DNA: IL-1 and IL-10 response in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells’, FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology, 38:165-172.

Leyer GJ, et al., (2009). ‘Probiotic effects on cold and influenza-like symptom incidence and duration in children’. Pediatrics, 124 (2):e172-9.

Morovic, W. et al (2017) Safety evaluation of HOWARU® Restore (Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM, Lactobacillus paracasei Lpc-37, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bl-04 and B. lactis Bi-07) for antibiotic resistance, genomic risk factors, and acute toxicity. Food chem toxicol. 110: 316-324

Ouewhand et al, (2009) ‘Specific probiotics alleviate allergic rhinitis during the birch pollen season’, World Journal of Gastronenterology, 15: 3261-3268.

Ouwehand et al, (2014) ‘Probiotics reduce symptoms of antibiotic use in a hospital setting: A randomized dose response study’. Vaccine, 32(4):458-63.

Paineau, D. et al, (2008), ‘Effects of seven potential probiotic strains on specific immune responses in healthy adults: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial’. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology, 53 (1):107-13.

Thompson et al, (2010), ‘The effect of fermented and unfermented milks on serum cholesterol’. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 36(6):1106-11.

Turner et al., (2017) ‘Effect of probiotic on innate inflammatory response and viral shedding in experimental rhinovirus infection – a randomised controlled trial’ Beneficial Microbes, 8(2): 207-215

West NP et al., (2014), ‘Probiotic supplementation for respiratory and gastrointestinal illness symptoms in healthy, physically active individuals’, Clinical Nutrition, 33(4):581-7.

Viborg AH et al., (2014) ‘A β1-6/β1-3 galactosidase from Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Bl-04 gives insight into sub-specificities of β-galactoside catabolism within Bifidobacterium’, Molecular microbiology, 94 (5):1024-1040.

Zhang H. et al, (2021). 'Effect of fermented milk on upper respiratory tract infection in adults who lived in the haze area of Northern China: a randomized clinical trial'. Pharmaceutical Biology, 59(1), 645–650.