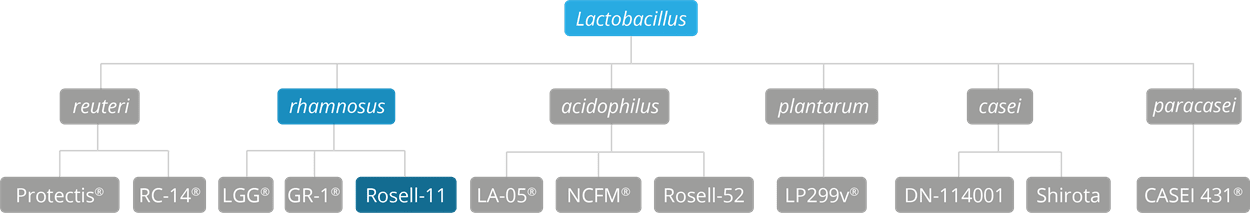

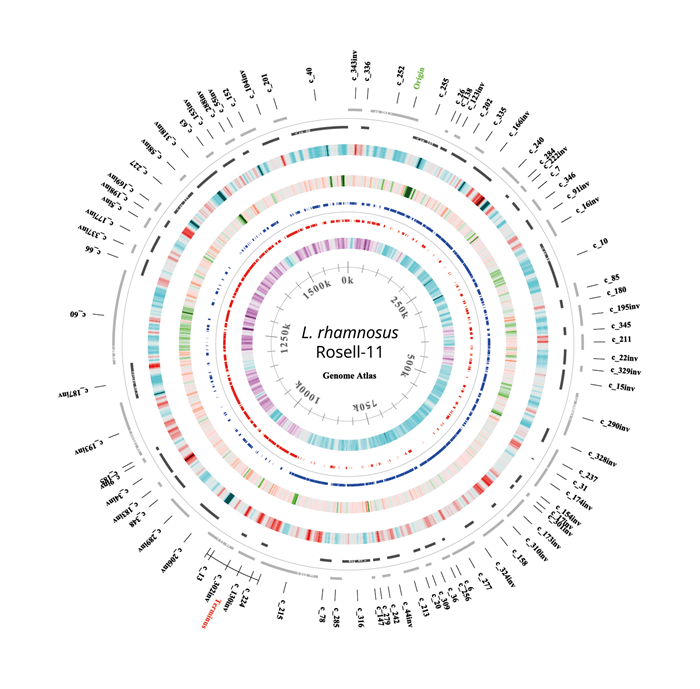

Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 is a very well-respected strain from the L. rhamnosus species of Lactobacilli, thought to be one of the most well researched species of probiotic bacteria. This particular strain is sometimes seen referred to as Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011; it was first isolated in 1976 from a dairy source, though strains from this species are regularly found as natural inhabitants of the vaginal and intestinal microflora (Wasowska-Krolikoeska K. et al., 1997). Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 is often studied alongside Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52 in a combination often referred to as ‘Lacidofil’. Both strains are listed on EFSA's Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) list. As of April 2020 L. rhamnosus has been officially reclassified to Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus so the full strain name may also be referred to as Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 (Zheng J et al., 2020).

The potential benefits of this strain have been researched in studies focusing on Helicobacter pylori infection, vaginal health, immune function, lactose intolerance, and anxiety; however, Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 has been selected for inclusion in this database of the world's best strains due to the extensive range of studies focusing on its effects for the relief of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Clostridium difficile infection, and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD).

L. rhamnosus Rosell-11 was isolated from a dairy starter culture. The ability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 to survive during transit through the human gastrointestinal tract has been investigated in a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study including 70 healthy subjects receiving an antibiotic combination of a*****illin-clav***nic acid (Nagulesapillai, 2015). The results showed that L. rhamnosus Rosell-11 was detected in 87% of the faecal samples using qPCR method. The survival of Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 has previously been shown in an open human trial including 14 healthy volunteers assigned to consume 4 capsules daily (each containing 2 billion cfu of L. rhamnosus Rosell-11 in a mixed culture) for a period of 12 days followed by a 12-day washout period. At the end of the capsule consumption period, high levels of Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 were detected in faecal samples from all volunteers, reaching a mean value of 7.1 log10 CFU/g of stool (Firmesse el al, 2008).

L. rhamnosus Rosell-11 has been evaluated for its safety. Toxicity studies were completed, and no toxicity was observed (Foster et al, 2011). In clinical studies on L. rhamnosus Rosell-11, there were no undesired outcomes when monitoring for side effects such as allergic reactions or intolerance (Rampengan et al, 2010). Evan et al (2016) demonstrated that safety parameters and adverse events were not significantly different between the intervention and the placebo.

In vitro studies using Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 have shown its ability to adhere to human intestinal epithelial cells, thereby inhibiting the adhesion of pathogens to the epithelium and assisting with their eradication (Sherman et al., 2005), (Wallace et al., 2003). Building on this research, human clinical trials have been conducted to further explore its potential to help with diarrhoea symptoms caused by antibiotic-associated gut microbiota disruption, and also diarrhoea caused by pathogenic infections by bacteria such as Clostridium difficile.

In one such gold standard, randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical trial, 146 healthy adults were given Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 alongside Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52. The participants were given a broad spectrum antibiotic alongside the probiotic supplement for one week, and then the probiotic was continued for an additional week following the antibiotic treatment. A control group was given a placebo supplement alongside the antibiotics, using the same regime. The results concluded that the group taking the probiotic formula suffered from AAD symptoms for a statistically significant shorter amount of time than those in the control group (Evans et al., 2016).

An earlier trial observed 244 children aged 0-17 years, who were all suffering from acute urinary, digestive or respiratory symptoms. A group of 117 children were given antibiotics together with the Lacidofil probiotic combination, and the other 127 children were given antibiotic therapy only. The results of this study showed that there was both a lower incidence and decreased duration of AAD with the probiotic supplement, as well as a decrease in levels of Clostridium difficile compared to the control group (Maydannik V. et al., 2010).

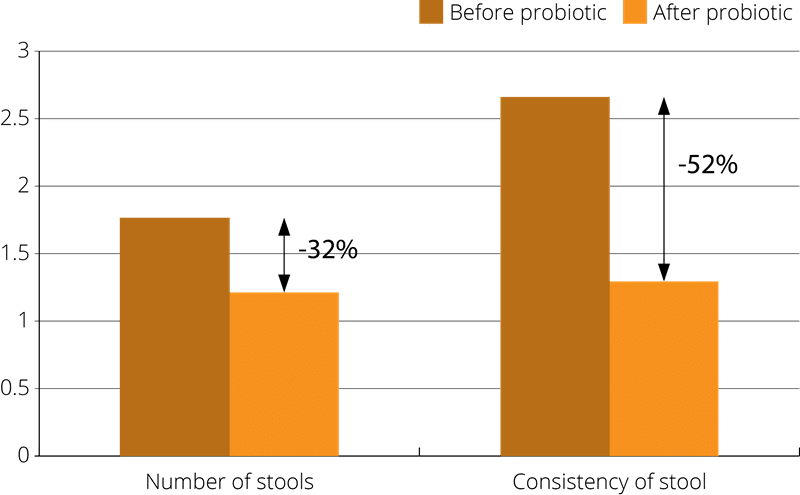

The probiotic combination Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 were again used in a large clinical trial to assess its efficacy for the prevention of AAD in adults. 214 patients with respiratory tract infections, who had already embarked on antibiotic therapy, were randomly grouped to either receive the probiotic formula, or a placebo, for 14 days. Patients were asked to record their bowel frequency and stool consistency on a daily basis. The results showed that those taking the probiotic maintained their normal bowel habits and function, to a greater extent that those taking the placebo, suggesting that these strains of bacteria help prevent AAD (Song et al., 2010).

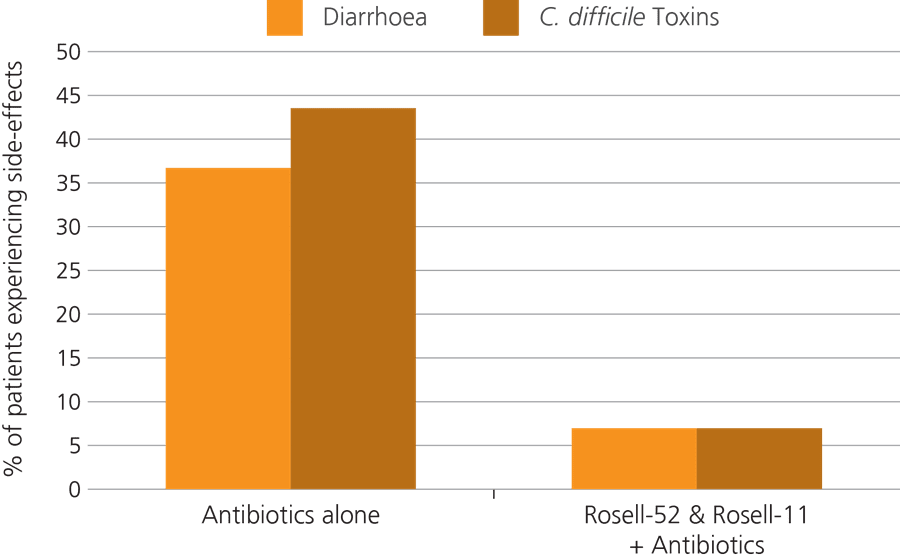

Another significant trial monitored 57 children who were taking antibiotics, to see if the addition of a probiotic given alongside the medication could help to reduce the risk of AAD.

The children were split into two groups, with half of them being given the probiotic combination of Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 and Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52, and the other half being assigned to a control group in which members were given the antibiotic medication only. It was found that 36.5% of those in the control group went on to develop AAD, whereas only 7.4% of children in the probiotic group developed this side effect (Ivanko O. & Radutnaya E., 2005).

Other Relevant Studies: Aryayev M. & Kononenko N., (2009), Dial S. et al., (2003), Doder R. et al., (2013), D’Souza A. L. et al., (2002), Gnaytenko O. et al., (2009), Jirapinyo, P. et al., (2002), Liskovich, V. et al., (2010), Marushko Y. & Shef G., (2007), Maydannik V. et al., (2008), Patsera M. et al., (2010).

Acute or chronic diarrhoea is a common complaint in daily clinical practice, and is often a primary symptom of gastrointestinal tract disorders. It is of particular concern in developing countries where it is a common cause of serious health problems, associated with a high mortality rate in both children and adults. The consumption of probiotics to alleviate or prevent acute episodes of diarrhoea is well-supported with a collection of clinical studies, however more research needs to be carried out to investigate details of methods of action (Simadibrata et al., 2013).

With this focus, a randomised, controlled clinical trial was conducted using 76 adult patients with acute diarrhoea. The subjects were divided into a treatment group, where members received the probiotic combination Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 alongside Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52 for 7 days, and a control group was given a placebo. The study concluded that there was a faster recovery rate in the probiotic group of at least one whole day. A greater improvement in the clinical symptoms (frequency of stools, stool consistency, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating, headache, fever and tenesmus) were also observed in the probiotic group, compared to the placebo, though the result was statistically significant in stool consistency changes only (Simadibrata et al., 2013).

An increasingly common digestive complaint, the precise underlying cause of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), is not well understood, and conventional treatments attempt merely to ameliorate symptoms. The composition of the intestinal microflora is believed to be a factor, and preliminary studies appear to suggest a positive role for probiotics. To demonstrate this effect, a 4 month clinical study administered the probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 alongside Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52) to subjects with IBS. The results illustrated that, of the participants who had suffered with chronic IBS for the last 10 years, 88% showed an overall reduction in IBS related complaints after the study period (Benes Z. et al., 2006).

Further relevant studies: Bruggencate T., (2015), Chayka V. et al., (2006), Firmesse O. et al., (2005), Kocian J. et al., (1994), Rampengan et al., (2010), Skorodumova et al., (2007), Tlaskal P. et al., (1995), Tlaskal et al., (2005), Wasowska-Krolikoeska K. et al., (1997), Zvyagintzeva et al.,(2008).

Helicobacter pylori is a common resident in the stomach, and in many people, it does not cause any problems; however, if conditions are ripe for its proliferation, it can become a factor in stomach ulcers and associated symptoms such as acid reflux. H. pylori typically lives in the stomach, where it is able to survive the harsh conditions by boring a hole into the stomach lining to ‘hide’ from the acid. Because of this hiding technique, it can be difficult to effectively eradicate this pathogen. The standard medical approach is a ‘triple therapy’ comprising two different antibiotics in combination with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), typically given for one week. This treatment is not always fully effective and H. pylori infection often recurs. The use of probiotics as an effective natural adjunct to conventional methods is being explored.

In order to assess their potential, a study was conducted which used the probiotic combination, Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 and Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52, alongside the standard triple therapy. The trial monitored 152 patients who had tested positive for Helicobacter pylori and who were suffering from typical symptoms. The subjects were divided into groups, where members were assigned to be given the probiotic combination alongside the 10 day triple therapy, or the triple therapy alone (control group). After 6 weeks, the participants were tested and it was found that, 72% of patients in the control group achieved a total eradication of the pathogen. In the probiotic group, however, the H. pylori eradication rate increased up to 92% (Bielanski W. et al., 2002).

Further relevant studies: Abaturov et al., 2014, Babak O., (2007), Gnaytenko et al., 2009, Plewinska E., (2006), Vdovychenko V., (2008), Ziemniak W., (2006).

Lactose intolerance is described as an inability to digest significant amounts of lactose, which is the primary sugar found in milk and other dairy products. Lactose intolerance usually develops from an insufficiency of the enzyme lactase, which breaks down lactose into simpler molecular forms that can be more easily absorbed into the bloodstream. Many probiotics are B-galactosidase positive, giving them a lactase-like action which helps with the digestion lactose in the intestines. There has been a small amount of research to indicate that probiotics may help to improve lactose tolerance, and the strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 is one of the probiotics which has been investigated for this purpose (Maladkar et al, 2009).

A related study used 19 patients with lactose intolerance giving them the probiotic supplement, Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 and Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52, to take at the same time as consuming a variety of different dairy products including milk, cottage cheese and Edam cheese. Lactose tolerance as well as stool consistency was measured both before, and after, the two week study period. The results indicated that taking the probiotic supplement increased tolerance of the dairy foods by a third. The improvement in lactose intolerance was particularly significant when the subject were consuming milk (Kocian J., 1994).

Further relevant studies: Chernyshov, (2009a), Chernyshov, (2009b), Kocian J., (1996), Rampengan et al., (2010).

There is a growing interest in the use of probiotics to help rebalance the microflora in areas outside of the intestines, including the uro-genital area. Populations of the delicate bacteria in the intimate area can become unbalanced due to a variety of different factors, including menstruation, sexual activity, hormonal changes, and medication such as antibiotics. Although you will see from the other database entries that other strains have been more extensively researched for genito-urinary health, there has been some limited clinical research using the Lacidofil combination for this purpose. In order to try to demonstrate the efficacy of these probiotics in maintaining the natural balance of the vaginal microbiota, a group of women were recruited to take part in a small trial. The women were all taking antibiotics following a caesarian procedure. Alongside their antibiotics, a total of 56 women were given the probiotic supplement, Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 and Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52, and 40 were given a placebo supplement. The results showed that 89.3% of those women in the probiotic group had no negative changes in composition of their vaginal flora compared to the placebo group who all did. Additionally none of them experienced antibiotic associated diarrhoea compared to the control group, where 10% of the women experienced AAD (Liskovich et al., 2010).

Further relevant study: Chayka et al., (2006).

Whilst, to date, no significant clinical trials have been conducted to demonstrate this effect, there is some promising evidence resulting from a collection of in-vivo studies which suggest that the combination of strains Lactobacillus rhamnosus Rosell-11 and Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52 could help to support immune function.

Further relevant studies: Gareau et al., (2007), Zareie et al., (2006), Verdu et al., (2008), Gareau et al., (2010), Huynh et al., (2015), Smith et al., (2014).

Another interesting area of study is the gut-brain-microbiome connection. Again, more research needs to be carried out, but a murine study indicated that the Lacidofil probiotic helped to normalise anxious behaviour and memory impairments in immune-deficient mice with HPA axis dysfunction. Corticosteroid hormone levels were used as the measure of HPA axis activation, and statistically significant levels of the hormone were observed in the probiotic group of mice compared to the control group (Smith C.J. et al., 2014).

Further relevant studies: Callaghan B. et a.,l (2016), Cowan C et al., (2016)

Authors: Information on this strain was gathered by Joanna Scott-Lutyens BA (hons), DipION, Nutritional Therapist; and Kerry Beeson, BSc (Nut.Med) Nutritional Therapist.

Last updated - 21st May 2020

As some properties & benefits of probiotics may be strain-specific, this database provides even more detailed information at strain level. Read more about the strains that we have included from this genus below.

Lactobacillus acidophilus strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus LA-05, Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM®, Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52.

Lactobacillus casei strains: Lactobacillus casei Shirota, Lactobacillus casei DN-114001.

Lactobacillus plantarum strains: Lactobacillus plantarum LP299v.

Lactobacillus reuteri strains: Lactobacillus reuteri Protectis and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14®.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains: Lactobacillus rhamnosus LGG®, Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1® .

Lactobacillus paracasei strains: Lactobacillus paracasei CASEI 431®.

For more information and the latest research on probiotics, please visit the Probiotic Professionals pages.

Abaturov et al., (2014), ‘Efficiency of probiotic therapy in children with antibiotic-associated bowel disorders and Helicobacter pylori infection’. Sovremennaya pediatriya, 2(58):2014.

Aryayev M. & Kononenko N., (2009), ‘Prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in patients with cystic fibrosis’. Odessa Medical Journal, 4(114):78.

Babak O., (2007), ‘The use of Lacidofil in treatment of duodenal peptic ulcers associated with H. pylori’. News of Pharmacy and Medicine, 5:24-25.

Bang et al., (2014), 'Effects of Korean Red Ginseng (Panax ginseng), urushiol (Rhus vernicifera Stokes), and probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 and Lactobacillus acidophilus R0052) on the gut–liver axis of alcoholic liver disease'. Journal of ginseng research, 38:167-72.

Benes Z. et al., (2006), ‘Lacidofil (Lactobacillus Rosell 52 & Lactobacillus Rosell 11) alleviates symptoms of IBS’. Nutrafoods, 5:20 -27.

Bielanski W. et al., (2002) ‘Improvement of anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy by the use of commercially available probiotics’. Gut 51 11 A98.

Bruggencate T. (2015), ‘The effect of a multi-strain probiotic on the resistance toward Escherichia coli challenge in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind intervention study’. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69:385-391 .

Callaghan B. et a.,l (2016) ‘Treating Generational Stress: Effect of Paternal Stress on Development of Memory and Extinction in Offspring Is Reversed by Probiotic Treatment’ Psychological Science, Vol. 27(9) 1171– 1180

Chayka V. et al., (2006), ‘Prevention of disbacteriosis in pregnant and women recently confined with surgical delivery’. News of Medicine and Pharmacy, 19:14-15.

Chernyshov P.V., (2009), ‘Randomized, placebo-controlled trial on clinical and immunologic effects of probiotic containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 and Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 in infants with atopic dermatitis’. Microbial Ecology In Health And Disease, 21:3-4.

Chernyshov P.V., (2009), ‘B7-2/CD28 costimulatory pathway in children with atopic dermatitis and its connection with immunoglobulin E, intracellular interleukin-4 and in****eron-gamma production by T cells during a 1-month follow-up’. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol.,. 23(6):656-9.

Chernyshov P.V., (2007), ‘Integrated treatment of infants, patients with atopic dermatitis’ Dermatology, 3:23-26.

Cowan C et al., (2016) ‘The effects of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus rhamnosus and L. helveticus) on developmental trajectories of emotional learning in stressed infant rats’. Transl Psychiatry 6, e823;

Dial S. et al., (2003), ‘Evaluation of the effectiveness of the probiotic Lacidofil (‘For those on antibiotics’) in the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhoea: pilot study’. Montreal, Canada.

Doder R. et al., (2013), ‘Outcomes of Clostridium difficile enterocolitis after administration of antibiotics along with probiotic supplement’. Medicinski Pregled, 66(5-6):209-13.

D’Souza, A.L. et al., (2002), ‘Probiotics in prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhoea: meta-analysis’. British Medical Journal, 324:1362-1368.

Evans M. et al., (2016), ‘Effectiveness of Lactobacillus helveticus and Lactobacillus rhamnosus for the management of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in healthy adults: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial’. British Journal of Nutrition, 116(1):94-103. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516001665. Epub 2016 May 12.

Firmesse, O. et al., (2005), Quantification after transit in human digestive tract of For those on antibiotics (Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Rosell 11 & Lactobacillus Acidophilus Rosell 52) consumed in a food supplement’. National Institute of Agronomic Research, Presented at Rome Conference on Probiotics.

Firmesse O. et al., (2008), ‘Lactobacillus rhamnosus R11 consumed in a food supplement survived human digestive transit without modifying microbiota equilibrium as assessed by real-time polymerase chain reaction’. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol.,14(1-3):90-9.

Foster T.A. et al., (2011), ‘A comprehensive post-market review of studies on a probiotic product containing Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011’. Beneficial Microbes, 2(4):319-334.

Gareau et al., (2007), ‘Probiotic treatment of rat pups normalises corticosterone release and ameliorates colonic dysfunction induced by maternal separation’. Gut, 56:1522-1528.

Gnaytenko O. et al., (2009), ‘Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea as a complication of antihelicobacter therapy in children’. Practical Medicine, 5:76-83.

Hong et al., (2015), 'Probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 and acidophilus R0052) reduce the expression of toll-like receptor 4 in mice with alcoholic liver disease', PLoS One, 10:e0117451.

Huynh K. et al., (2015) ‘Administration of probiotics normalizes deficits in the microbiota-gut-brain axis induced by DSS-colitis’. Poster winner at Experimental Biology Boston 2015

Ivanko O. & Radutnaya E., (2005), ‘Lactobacillus acidophilus reduces frequency of diarrhoea caused by toxins Clostridium difficile A+B in children treated by antibiotics’. Zaporozhye Medical Periodical, 2:21-23.

Jirapinyo, P. et al., (2002), ‘Prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in infants by probiotics’. J. Med. Assoc. Thai; 85 (S2):S739-S42.

Kocian, J., (1994), ‘Lactobacilli in treatment of dyspepsia in dysmicrobia of different etiology’, Vnitrni lekarstvi, 40(c2):S.79-83.

Kocian J. (1996) ‘Further Possibilities in the Treatment of Lactose Intolerance: Lactobacilli’ Prakticky Lekar (General Practitioner). Vol. 74. pp. 212 – 214

Liskovich V. et al., (2010), ‘Efficiency of Lacidofil-WM for prevention of vaginal dysbiosis and antibiotics-associated diarrhoea in puerperas after caesarean operation’. Health, 1:63-66.

Maladkar M. et al., (2009), ‘Evaluation of The Efficacy And Safety Of Probiotic Formulation With Zinc Enriched Yeast In Children With Acute Diarrhea’. The Internet Journal of Nutrition and Wellness, 9(2).

Marushko Y. & Shef G., (2007), ‘Current status of antibiotics-associated bowel disorders issue in children’. Perinatology & Paediatrics, 4:65-68.

Maydannik V. et al., (2008), ‘Prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea’. Paediatrics, Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 1:63-65.

Maydannik V. et al., (2010), ‘Efficiency and safety of Lacidofil in children with antibiotic-associated diarrhoea caused by Clostridium difficile’. Pediatrics, Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 3:53-57.

Mukerji S.S. et a.l, (2009), ‘Probiotics as adjunctive treatment for chronic rhinosinusitis: a randomized controlled trial’. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg., 140(2):202-8.

Nagulesapillai, V. 2015. Detection and Quantification of Strain Specific Probiotics in Clinical Fecal Samples of Healthy Adults on Antibiotic Treatment by Quantitative PCR. Poster presentation. Lallemand Health Solutions.

Patsera M. et al., (2010), ‘Using probiotic strains Lactobacillus acidophilus R0052 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 during pulmonary tuberculosis in children, complicated by antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile intestinal infection’. Zaporozhye Medical Journal, 12:30-33.

Rampengan et al., (2010), ‘Comparison of efficacies between live and killed probiotics in children with lactose malabsorption’. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 41: 474-481

Sherman PM., et al., (2005), ‘Probiotics reduce enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7- and enteropathogenic E. coli O127:H6-induced changes in polarized T84 epithelial cell monolayers by reducing bacterial adhesion and cytoskeletal rearrangements’.

Infect. Immun., 73:5183-8.

Simadibrata et al., (2013), 'Revealing the effect of probiotic combination: Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus acidophilus (Lacidofil®) on acute diarrhea in adult patients', Journal of Clinical Medicine and Research 5:23-28.

Skorodumova et al., (2007), ‘The feasibility of using probiotic Lacidofil® in infants with diarrhoea of infectious origin’. Clinical Pediatrics, 2:159-160.

Smith C.J. et al., (2014), ‘Probiotics Normalize the Gut-Brain-Microbiota Axis in Immunodeficient Mice’ American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 307(8):G793–G802.

Song H. et al., (2010), ‘Effect of probiotic Lactobacillus (Lacidofil® Cap) for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea: a prospective, randomised double-blind multicenter study’. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 25:1784-1791.

Tlaskal, P. et al., (1995), ‘Lactobacillus Acidophilus (‘For those on antibiotics’ formulation) in the Treatment of Children with Gastrointestinal Tract Illness’. Cesko-Slovenska pediatrie. 51:615-619.

Tlaskal et al., (2005), ‘Probiotics in the treatment of diarrhoeal disease of children’. Nutrition, Aliments Fonctionnels, Aliments Santé 3:25-28.

Plewinska E. et al., (2006), ‘Probiotics in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in children’. Gastroenterolgia Polska, 13(4):315-319.

Verdu et al., (2008), ‘The role of luminal factors in the recovery of gastric function and behavioural changes after chronic Helicobacter pylori infection’. American Journal of Physiology – Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 295:G664-G670.

Vdovychenko V. et al., (2008), ‘Effectiveness of quadra therapy probiotics in patients with duodenal ulcers’. Current Gastroenterology, 43:90-92.

Wallace T.D. et al., (2003), ‘Interactions of lactic acid bacteria with human intestinal epithelial cells: Effects on cytokine production’. Journal of Food Protection, 66(3):446-472.

Wasowska-Krolikoeska K. et al., (1997), ‘Clinical assessment of L. acidophilus’. Report for Institut Rosell Inc.

Zareie et al., (2006), ‘Probiotics prevent bacterial translocation and improve intestinal barrier function in rats following chronic psychological stress’. Gut, 55:1553-1560.

Ziemniak, W., (2006), ‘Efficacy of Helicobacter Pylori eradication taking into account its resistance to antibiotics’. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 57:123-141.

Zheng J, Wittouck S. et al., (2020) 'A taxonmonic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae'. Int.J.Syst.Evol.Microbiol, 70(4): 2782-2858. DOI: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004107

Zvyagintzeva et al., (2008), ‘Correction of disbiotic disorders in irritable bowel syndrome’. Current Gastroenterology, 42:72-75.